I got my permit from the Pa. Department of Environmental Protection to operate an on-farm composting site utilizing black soldier fly larvae at the end of June in 2020. In that time, I took in 9,130.5 pounds of food wastes.

I had not run any auxiliary heat, other than the heat bulbs in the fly habitat. The collective heat of the bins sustained temperatures in the 80s. Even the concrete floor hovered around 70 degrees Fahrenheit, only dropping to 40 degrees right at the doorway. I actually had to cool the room in the month of December with and air condition, one of the models that also act as a heat pump and dehumidifier. A standalone dehumidifier works much more effectively to pull moisture from the air, and I purchased one for the larvae room.

So, what’s next?

This winter — feeling like the longest winter — has offered some insight into how I’d like to see the operation run in the future. Everything is harder in the winter, especially when attempting to keep a large colony of insects alive and thriving. As I went into the winter of 2020, I had the most larvae I’ve ever had at one time. In a 12’x12’ insulated room, I had 36 plastic bus bins of ravenous larvae which were able to consume 200 pounds of food a day. A few things happened: 1) the larvae began generating significant heat in their bins (one registered 116 degrees Fahrenheit which had to be remedied to ease their discomfort), 2) they began seeking food and escaping, and 3) the humidity was so high in the room that as they escaped up slippery sides of the bins, they piled on the floor and would scale the walls — yet again.

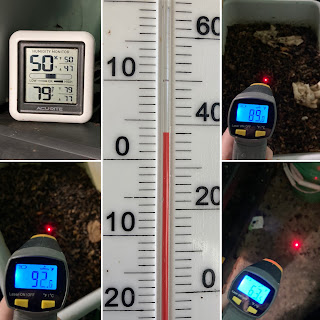

|

| Center shows the outside temp while the ambient room temperature and humidity remain quite high |

I had not run any auxiliary heat, other than the heat bulbs in the fly habitat. The collective heat of the bins sustained temperatures in the 80s. Even the concrete floor hovered around 70 degrees Fahrenheit, only dropping to 40 degrees right at the doorway. I actually had to cool the room in the month of December with and air condition, one of the models that also act as a heat pump and dehumidifier. A standalone dehumidifier works much more effectively to pull moisture from the air, and I purchased one for the larvae room.

To make a more hospitable winter processing space for food buckets and washing, my parents and I hung a double panel of old greenhouse plastic. The ceiling of this plastic room was lined with a patchwork of reflective insulation and leftover larvae room insulation. It is much improved from my cramped work station in the larvae room this time last year.

|

| Repurposed greenhouse plastic created a comfortable space and Dad framed out a repurposed closet door for me to use |

|

| A little duct tape to the ceiling insulation adds personality |

|

| The coldest days tend to be the sunniest so it's a great space to work and not feel like I'm in a cave |

As soon as 2021 came around, I had all of the larvae transition into their next life cycle, which meant their food waste consumption dropped dramatically. I was down to three or four bins by Jan. 8. The room temperature had to be maintained with a space heater at that point. All the food wastes I brought in went into a compost pile. Tending to a compost pile through snow and frigid days was not an ideal situation for me. But regular temperature monitoring showed consistently high temps: 174 degrees Fahrenheit as the hottest. That is a very hot pile, but in an era where we have become more sensitive about germs and pathogens, I think this will comfort anyone who might be concerned. And there is a lot of biology in this compost pile, even during the coldest stretch of January. Red wiggler worms can be found six inches down from the surface. Other insects work busily through the pile. One of the barn cats perched on top of the covered pile to stay warm on a very chilly day. It’s thrilling to turn the pile and have the steam billow out, and all I fantasize about how to tap into that energy and heat all kinds of elements: water, floors, rooms, buildings.

|

| The day that this was taken was right at the start of a very heavy snowfall. The toes in the photo belong to compost cat Lion who is no longer with us and I miss him |

I have been very conservative about how I acquire resources. The water I use to wash buckets was diverted from the barn roof on a precious rainy day in November, captured in a 270 gallon plastic tote. Even the coldest days didn’t freeze that water, but the spigot did freeze closed on me. I had a backup supply: as I developed a processing/washing routine, I had filled several 5 gallon buckets with water and stacked them in the larvae room for a couple of reasons. It acted as a heat battery, regulating the temperature of the air, and it was also a lot easier to heat water that started at 72 degrees versus 40 degrees. Heating water for washing is as simple (rudimentary) as turning on a propane space heater and setting a metal 5 gallon bucket in the line of fire for an hour or so.

On Feb. 16, I decided that the larvae room was functioning at a consumption rate that again meant that the space heater was no longer required but the dehumidifier was. At this very moment, the room has 23 larvae bins able to eat 70 pounds of food a day. The dehumidifier also supplements the water I use for washing, pulling about 3 gallons from the air a day. I’ve only used a third of the 270 gallon tank at this point.

So that series of anecdotes draws me to the grand vision: a land rejuvenation facility with complete resource management that utilizes solar and wind. This bioconversion process reduces waste volume 50-80%. This wouldn’t have to be a huge building to house the larval operation, and while it does require a lot of energy to generate heat, every bucket of food is fuel and the furnace is larvae. Additionally, I’d love to have a greenhouse — heated via compost — on site with native plants for sale.

I want to offer products for building soil (compost and frass) and products for homesteaders (larvae for chickens). I want to provide a service for the eco-conscious (pick up service for home and business.) I do not want to call anything a waste in this facility: it is all resource in transition. And what I want to see most is a company that can provide well-paying jobs for the community and return healthy resources back. Full Circle.

I dream of this every time I stand in my plastic-walled room with the propane space heater keeping the chill off my back. I have a million concepts that might work but I need help. I need a like-minded soul with the patience of a saint and a willingness to get elbow-deep in larvae shit and sweep up pounds of larvae from the floor when the situation arises. This is a tall order, not for the faint of heart. If any of this resonates with you, I would love to hear your thoughts. It feels as if I’m trying to plan a new patio on a house while my kitchen is presently on fire: it is very hard to consider the upgrades when survival is taking all my energy. This business, like my larvae, would like to thrive, not just barely survive.

Lots of larvae,

Aubrey

On Feb. 16, I decided that the larvae room was functioning at a consumption rate that again meant that the space heater was no longer required but the dehumidifier was. At this very moment, the room has 23 larvae bins able to eat 70 pounds of food a day. The dehumidifier also supplements the water I use for washing, pulling about 3 gallons from the air a day. I’ve only used a third of the 270 gallon tank at this point.

So that series of anecdotes draws me to the grand vision: a land rejuvenation facility with complete resource management that utilizes solar and wind. This bioconversion process reduces waste volume 50-80%. This wouldn’t have to be a huge building to house the larval operation, and while it does require a lot of energy to generate heat, every bucket of food is fuel and the furnace is larvae. Additionally, I’d love to have a greenhouse — heated via compost — on site with native plants for sale.

I want to offer products for building soil (compost and frass) and products for homesteaders (larvae for chickens). I want to provide a service for the eco-conscious (pick up service for home and business.) I do not want to call anything a waste in this facility: it is all resource in transition. And what I want to see most is a company that can provide well-paying jobs for the community and return healthy resources back. Full Circle.

I dream of this every time I stand in my plastic-walled room with the propane space heater keeping the chill off my back. I have a million concepts that might work but I need help. I need a like-minded soul with the patience of a saint and a willingness to get elbow-deep in larvae shit and sweep up pounds of larvae from the floor when the situation arises. This is a tall order, not for the faint of heart. If any of this resonates with you, I would love to hear your thoughts. It feels as if I’m trying to plan a new patio on a house while my kitchen is presently on fire: it is very hard to consider the upgrades when survival is taking all my energy. This business, like my larvae, would like to thrive, not just barely survive.

Lots of larvae,

Aubrey

|

| (and kitten Uno) |

I wish I could help you with this but I'm in Arkansas. I've been binge-watching your youtube videos and now I'm working on your blog. I really like what you're doing.

ReplyDeleteA video idea you might be into: if someone else were interested in starting the same operation as you, what would they need to do? It would cover basic equipment, basic processes, etc.

Also, remember that a big part of the gardening/homesteading/composting/urban-farm thing on YouTube is about selling a lifestyle, as gross as that is. The whole "hey you could do this too and you should!" - shtick, with a Patreon link slapped on it. Obviously the goal is more noble than that, but might be worth putting some time into.

But yeah, I'd like to see a "this is how to start your own soldier fly operation" video. And a "if I were to start over from scratch, this is how I'd do it" video.